Displaced

“Displaced” FX Harsono/ Curatorial Preface

After the 1970s, we need to see the development of FX Harsono’s work to learn how an Indonesian artist perseverantly and tirelessly voices critics to various things. We know that FX Harsono has placed himself and his works since mid 1970s in Indonesian modern visual art. The place for his initial works and became known lies in the resistance against the mainstream of painting looking for nationalistic personality in the 1970s.

As a young artist, a student of the academy of art, he formed a visual art group that later proved to be the pioneer of a pluralistic aesthetic and judgement within the arts. This group afterwards realized the tendency and goals within their group as a “movement”, that is, Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru/GSRB (The New Art Movement).

We generally could understand the difference between “movement” as this group’s tendency intended and what is called a ‘school’ that shape the development of visual arts in previous periods. In the interpretation of avant garde art (ists) a movement tends to show aggression or agitation towards a tradition, whether a tradition originating from a master or a teacher, academy, or even a form of collective called society or public. The teachings or thoughts coming from those being opposed were considered to be disadvantageous or even hindering development. The tendency to agitate is a spirit can be said attached in the characteristics of a movement that is antagonistic in nature.

A movement is definitely different from a ‘school’ (we know ‘schools’ such as Bandung group or Yogyakarta group) that sees it is important to maintain and pass on a system of working or the school itself; that has vitality but “immune to a change”, while requiring a number of apprentices. A movement – and the followers – do not understand culture as a kind of encyclopedia as schools do, but rather as a creation, or as “the center of activity”. In sentences we often hear lately, a school tends to see culture as a noun, while a “movement” sees it as a “verb” thus more dynamic.

Other schools work within and for trancendental aims, that often are not determined or made by the school itself. While movement rationally have an immanent aim as its base, inherent in the movement itself. Obviously, a school tends to teach or pass something on, but what, for example, could have been taught or passed on from a movement?1

Another thing to add to a movement is the temporariness of the movement itself. In GSRB (1974-1979) for example, the statement during dissolving the groups in the movement was consciously and rationally and with particular considerations showed a part of the original movement they believed in.

The current in painting that FX Harsono and his friends was going against was the painting that tries to search for national identity in visual arts, in line with national personality, formulated during the New Order.

Visual art trying to search for national identity could be seen as an inseperable part of the argumentation of political culture that was marked by the efforts to handle “cultural politics that insists on determining how (national) culture has to be formulated and practiced according to political aspirations. If national politics wants to search for its identity in national unity, then national culture tries to search its identity in cultural unity. Cultural unity is none other than Indonesian national culture, formulated by some people as the summits of cultures originating from the regions.2

May be the painters trying to search for national identity in their works through sources of tradition they have scavenged will consider the selected sources as summits needing to be unified.

For Harsono, resisting a mainstream in visual arts at that time may be was easier to understand, at least internally within the environment of the artist themselves. But how this resistance was prevented from becoming an exclusive resistance or a pseude-intellectual, for example, is a question nevertheless important to be asked. At least, how the resistance can be meaningful and can be understood by the society? Even though these thoughts generally does not exist among the resisters and innovators, Harsono’s questions will spark a further debate on the relations of art and society.

If the resistance of art and artists have a social rationality, how would this rationality be understood by society that they imagined? In other words, would the rationality of resistance in the arts – to certain level – will also consider the society’s rationality and take it into account?

As an artists in a such a situation, FX Harsono seems to be struggling to formulate his own thoughts. He writes in a short essay – his first – about two basic patterns of thinking in Indonesia’s visual art development he and his friends have proposed.

Their two basic thinking was first, the search for stagnation of Indonesia’s “dependent, unqualified” and “identity-less” visual arts. The second way of thinking is the concern to yield new works that never existed in Indonesia.

Both ways of thinking that tends to be the base of the movement and the reason of development believed by GSRBI according to Harsono contains danger. The first danger is the excessive obsession for tendency of conceptualism or intellectualism for the sake of bringing up something new. The second danger is newness for the sake of newness itself (this certainly is one of the tendency in avant-gardism), that never brings advantage unless an aspiration of improvement “to leave the old”, and “push themselves to keep up with other nations’ visual arts”.

In Harsono’s thoughts, by observing, integrate and criticize both ways of thinking and became a new consciousness (both for the artist as well as for a movement) the danger of being too ‘extreme’ can be avoided and will at last bring newness, not only with solid ground but also useful.3

After several years, the movement was declared as dissolved and each member works solitarily to survive in a difficult and challenging city. After two decades of the birth of GSRB, FX Harsono himself seems to have realized the development of the post-movement situation. He then wrote:

“Almost every avant-garde artist works outside the creation of their individual arts. They certainly can’t live from their art, as painters, sculptors or designers. Initially the struggle to overcome life is not acknowledged as a way of life underlying the artistic attitude, yet later a new consciousness emerged among avant-garde artists, that income generating activities can bring up a creative spark of idea and the discovery of new idioms in visual arts. (…) If several ex-Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru artists are still active, it means they had struggled for almost 20 years, it doesn’t mean that their struggle is over. Because of the absence of infrastructure for novel visual art, then the whole activity is meaningless because the new values are not yet disseminated…”4

After a while, artistic activities from ex-members of GSRB remained unheard, also from FX Harsono. During 1987-1991 Harsono continued his studies at Painting Department Jakarta Art Institute (IKJ). It was during this period that he managed quite a successful graphic design studio and took part in several group exhibitions of graphic design. His activity as artist was not as active as in the seventies. May be the same thing happened with other ex-GSRB members — and the downturn in Harsono’s creativity — was actually the opposite of what he wrote. The challenge for these artists was not an idealism where “income generating activities can bring up a creative spark of idea”, but rather a pragmatic activity attacking most of them, where “a creative spark of idea was part of income generating activities”.

Moelyono, an artist from the younger generation wrote a critic to the downturn of ex-movement artists that ceased to show a passion in visual art works, “… Twenty years now, the pioneers once long-haired heroics, now wears Korpri [Indonesian civil servant association – trans.] outfit. He has wife and children. Other organizers became journalists, graphic designers, painters, housewives. Several organizers said that Novel Visual Art is bankrupt, in the face of feeding wife and children. Exhibitions used to be shut by police, and now there are only wives and children.5

In 1985, together with some artist friends who had similar idea and concerns about forest condition and environment in Indonesia, FX Harsono reemerged and joined an exhibition called “Proses ‘85” at Galeri Pasar Seni Ancol, Jakarta. Harsono together with friends wrote an essay for a discussion before the exhibition – all of Harsono’s exhibited work were installation works – about their works in the exhibition. He criticized artists who “didn’t try to raise deeper issues, caring more about the society” and “the errosion of artists’ social role”. He expected a meeting of social layers of audience and artists in the objects used by artists in their works by involving the social millieu of the objects themselves.

It’s impossible to picture Harsono and his works without at the same time picturing the condition and social pathology of the society he observed and criticized. The society is the genealogy of his works. The artist is the subject as well as visible the object unable to distance himself from great discourses of social life. Even if the subject is able to draw a distance with the society (if not how would they analyze?), the object of art in the end can not do the same. And if the subject is very much related to problems of the society, can an aesthetic object or text be detached from the creator? In this sense, for Harsono the subject and object he created are one; their circles would meet in a surface of social circle. From that comes the artist subject’s rationale of creation and the source of legitimacy of the art work itself.

Thus, for Harsono, an art work is born through a treaty between artist and its society: good news descended from an “artist-priest” to all of us in a big plan of concern and savior of mankind living in the endless desert of social pathology.

If the artist works, “Object to one’s artistic work is not a mere “object accusative” for an artist’s obsession. Object and artist is at equal positions in facing and conversing in the effort to overcome challenge or problem arose in their environment. Is it possible that this exists in the life of our visual art creation? …It is possible and it must exist,” wrote Harsono.6

The process of creating art work seems to be schematically, rationally and naratively explicable, even from the artist himself, something that very rarely happen in the environment of Indonesian artists who normally would surrender his artistic form and thinking to “regime of inspiration”. In short, in Harsono there is a strong tendency to shove away what is called “mystery” in the arts, that relates to fascinating and also terrifying dimensions of reality that sometimes shakes the artist, and label it as a “problem”, relating it to the totality of social issue matrix that can be formulated and solved together by everyone involved.

With the illustrated quotes above, we would understand more about what has an artist capture with his sensitivity in his statement for his first solo exhibition in 1994:

“(…) Consciousness as an artist is realizing that human being can’t deny its fate as a social creature. McLuhan said that an artist is “antenna of society”, the artist as the receiver of vibration from the society. One can function as the healer of the society. One is the priest or even speak about what will happen in the society… Moving from this consciousness, social and cultural issues can not be detached from the creation of art work: creativity in art must be able to reflect social issues, as well as raise the audiences’ awareness. Social issues exist in our life. At this point, my art is a form of expression trying to remind the audience of the problems we are facing together: creation of art is an materialization of commitment…”7

+++

This time FX Harsono comes back after pondering for long about what is best for him as an artist who still considers himself as concerned about what is happening around him. Yet at the same time the artist also directs his question exactly to himself, the form of art and medium he so far work with. Just like his statement during his debut in 1970s, he is once again driven to use “utilitarianism”, but now it evolves into a backlash that throws questions, as if de-legitimizing representation in his previous works.

Harsono realizes and notes significant historical moments, and they yield new considerations for him and places them in a transitional situation: the shift of political power in 1998, the unpredictable up and downs of societal situation and finally his personal considerations on identity, including his self identity.

The place where he lies until now is no more felt as a place, the place doesn’t give him comfort and roots. Harsono believes that the place he sets himself at until now –where the others also place him – is not the suitable place for him. At the same time he is asking himself, where is “the righteous place” for him today, afterwards, and in the future?

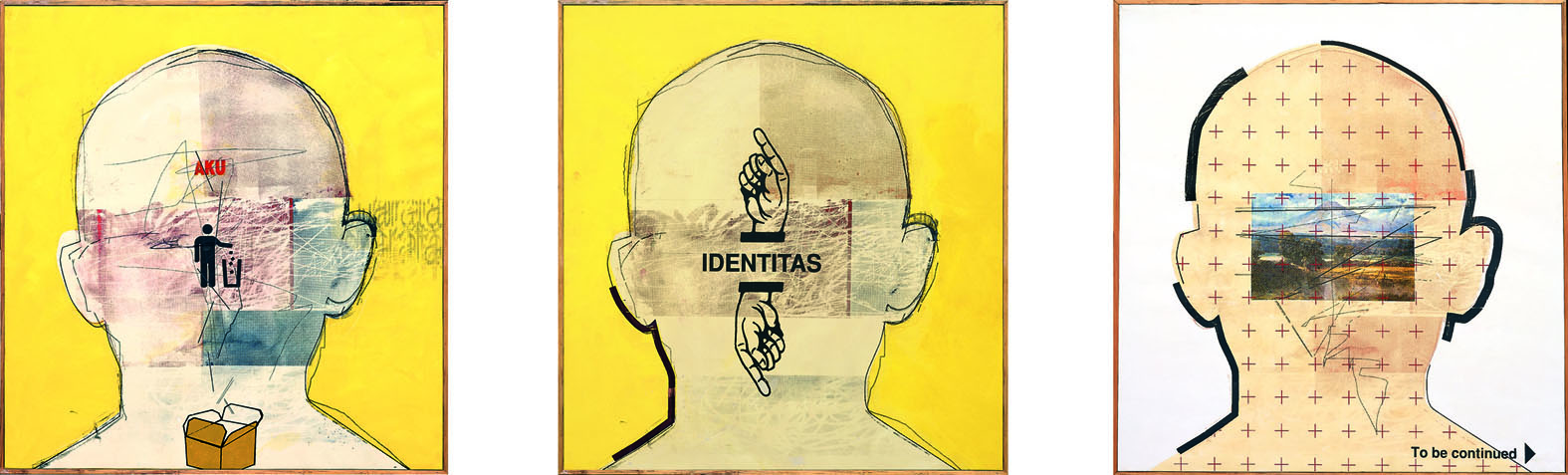

Harsono’s works stresses less on the issues of power and injustice. Although he still retains such issues, it is clear that he is zeroing into the issues of identity within his self as an artist, which he claims to be more cultural than political. Is the “political subject” with all the rationality and personal narratives melts inside him? Would he like to bring himself forward as “lingual subject” enjoying the game of language itself?

In the postmodernist terms, has a de-legimization occurred that triggered mainly by a demand of legitimacy itself that remains unproven until today? Is he going through an internal erosion within the legitimacy of “scientific” principals or “believe” on the arts and society that he so far believes in?

Are we seeing, in Harsono’s current works, a shift of purpose of the act itself towards the media of materializing the acts? It seems that, exactly by loosening the tensions in the surface of artists’ circle, arts and society he once imagined, each sphere becomes more free: the network loosens and every sphere finds an arena for their respective games…

Social ties can be linguistic in nature, but it is not tied in a single knot. The ties forms a texture that was formed by the crisscross of linguistic play, each will follow different rule. Quoting linguistic philosopher Wittgenstein, our language can be seen as an ancient city consisting of many intersection of narrow streets and fields, old and new houses, and houses with so many additions from many era. All is situated in an environment of many sectors with streets so straight and orderly and uniform houses. (…) How many houses or street would it take for a city to become a city?8

This time Harsono changes his working strategy by following different rules of games in different media: photoetching, silkscreen, xerography, photography, digital print, textual quotes and variations of them all.

Isn’t he actually trying to “rediscover” an old city he once lived in, that he now enjoys through winding road: the print media he is very familiar with as graphic designer. He understands how to use many softwares, identifying images and designs, the collection of icons, picture and photography manipulation, the processing of various effect of a ready image and created ones, copying and editing all of them at the same time. They show a trace of virtual nature inherent in the web gluing together a universe: a visual collection on the internet. His current graphic works actually shows important shifts in views and his works, which are worth observing.

+++

Harsono’s works in this exhibition hardly retain the image of the nature and tools of violence as often presented in his previous works. We no longer see the strength of image and militaristic narratives through a parade of guns or pistol images (since 1970s he already used these icons). As substitutes, he uses the images of fire that brings our association closer to psychological as well as cultural symbols.

It is true that, contrary to mass killings using various tools and weapons throughout Indonesian tragic history of 1965-1966, fire has been the psychological symbol of amok – maybe this has been part of the artist’s dreadful consciousness – in the May 1998 riot before the fall of the New Order Regime.

If the corners of Harsono’s works are full of the image of fire and bodies lying helplessly, the bodies are sometimes the image of himself. Does he represent the body of the victims, or “scorched” by something else? The image of vaguely smiling wooden masks becomes a fantastic element that brings up a riddle in his work. In the other part of his work the masks are also scorched – as if turning into firewood – together with lying scorched bodies (“Api 1”, 2000).

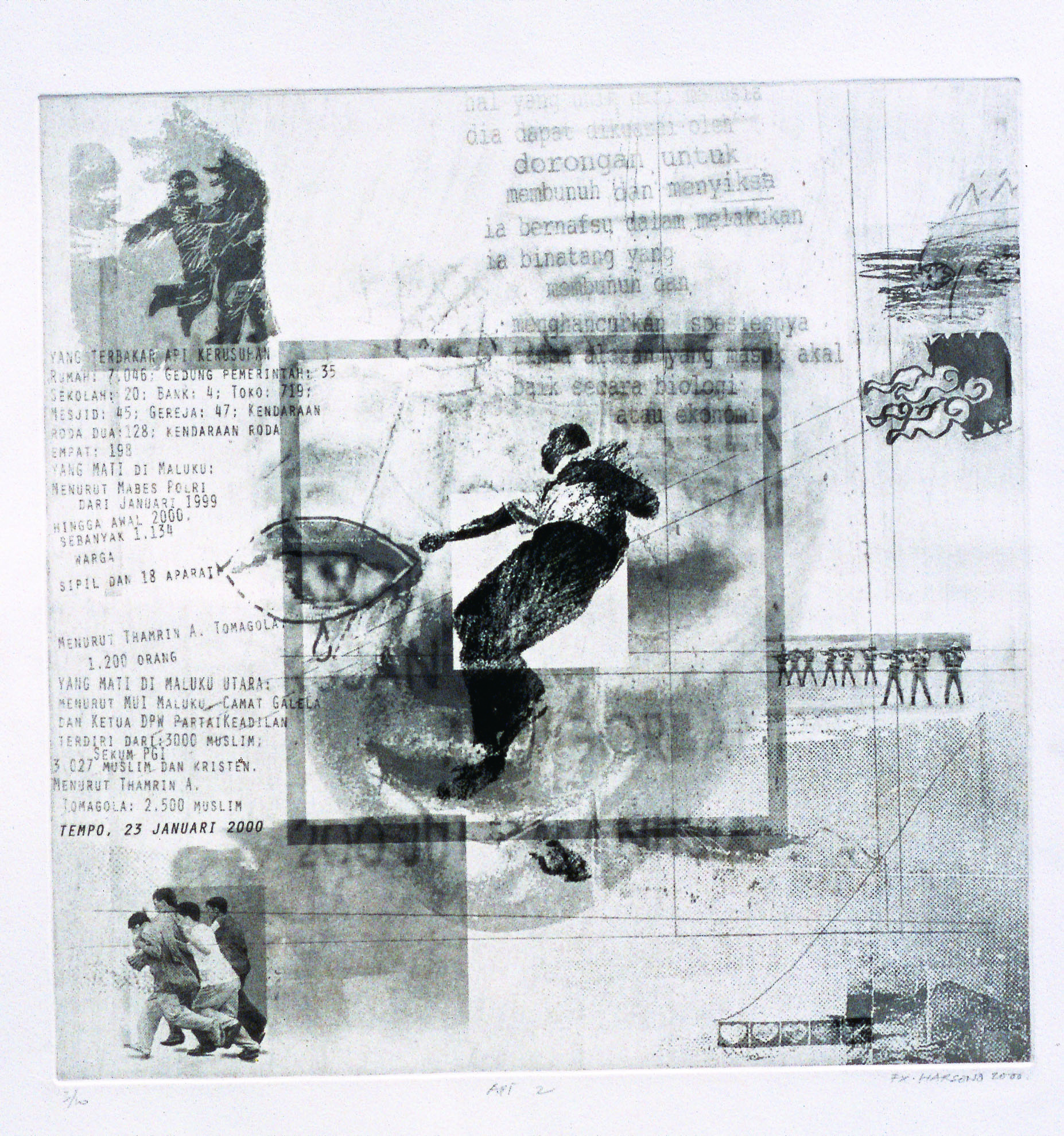

The masks surely gives an image of concealment of truth, mysteriously protecting the identity of whoever is using it. As a universal symbol, masks here are no longer used to assert cultural identity. Seeing masks in Harsono’s works together with the artist’s concern puncturing the darkness he sees behind the fire, would leave question marks inside us. Will the investigation of May 1998 riot, that has crushed thousands of buildings, vehicles and costing the lives of about 1200 people be left concealed behind the curtain?9 Do our faces look like masks: obedient and refined officers, the teaming mass and the artist himself? The are no sign of artist heroism visible in these works. To give substance to his masks, Harsono quotes the sentence of Erich fromm on the psychology of amok in human beings that enjoys destroying their species without a rational reason like one can read in “Api 2” (2000).

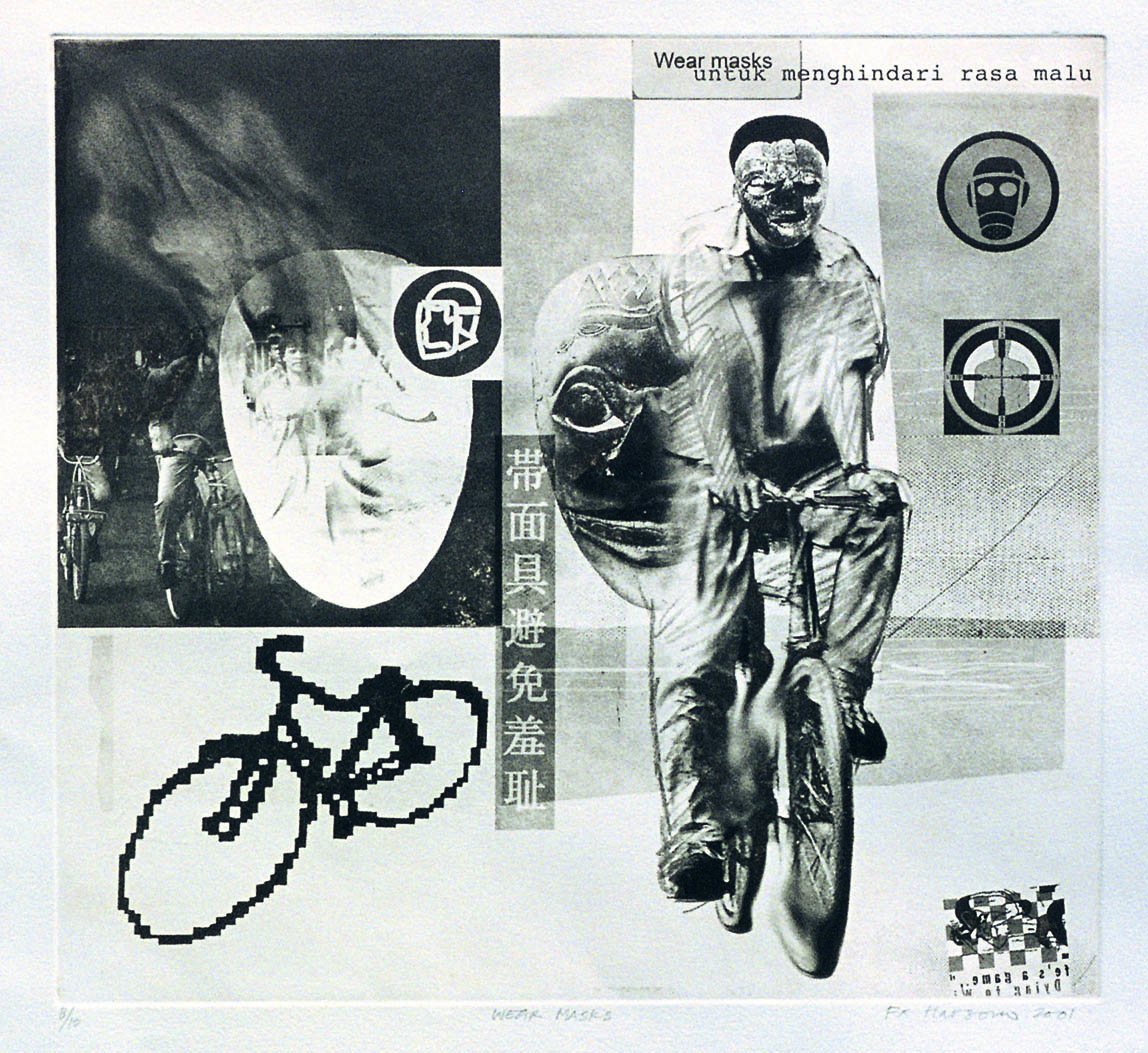

The image of masks in these works are from the same mask he once used in his installation work, where Harsono cut the mask in the mouth. In “Wear Mask” (2001) he places the image of the mask with clear statement, “avoiding embarassment”, side by side with a picture or portrait of himself wearing a mask and riding a bicycle. Is he speaking about himself who is an ambiguity compared to other members of society?

A line of Chinese characters are presented distinctly with similar meanings as if celebrating the return of various Chinese identity – that already shaped half of his identity – after being banned for 32 years. The square spaces lying on top of each other, narrow, broad, sharp or soft dividing Harsono’s pictures and indicating the maze of each determination of a rigid border.

Now, everyone and especially the artist can open their mouth as wide as they want, Open Your Mouth” (2001). But do we still believe in what comes from a mouth forced to be open wide like that?

Through photographis image and photo etching technique that he uses, Harsono presents a raster effect in his print works. These effects was blown up to rough dots as used by pop artists like Poke, Lichtenstein, and Warhol, to show the image of mass media among other things, which are considered to be the continuation of modernist tradition in using everyday objects. By presenting such images, the individual trace of the artist can even be erased.10 Even though the effect is not so obvious in Harsono’s work, but it is clear that he has used it to show mechanical reproductive effect as an artistic gesture in his photo etching work.

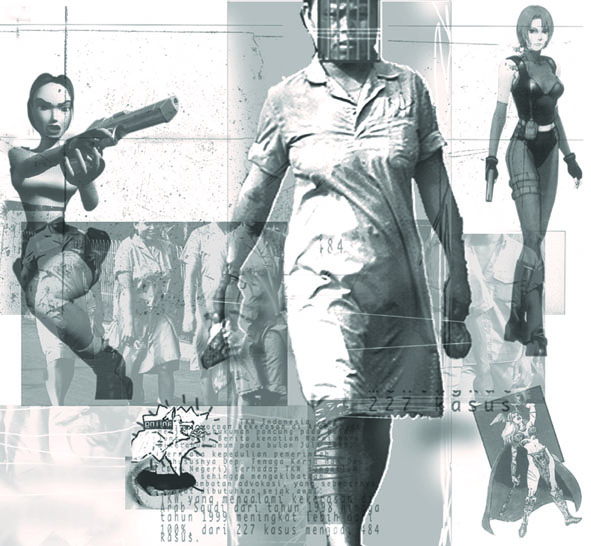

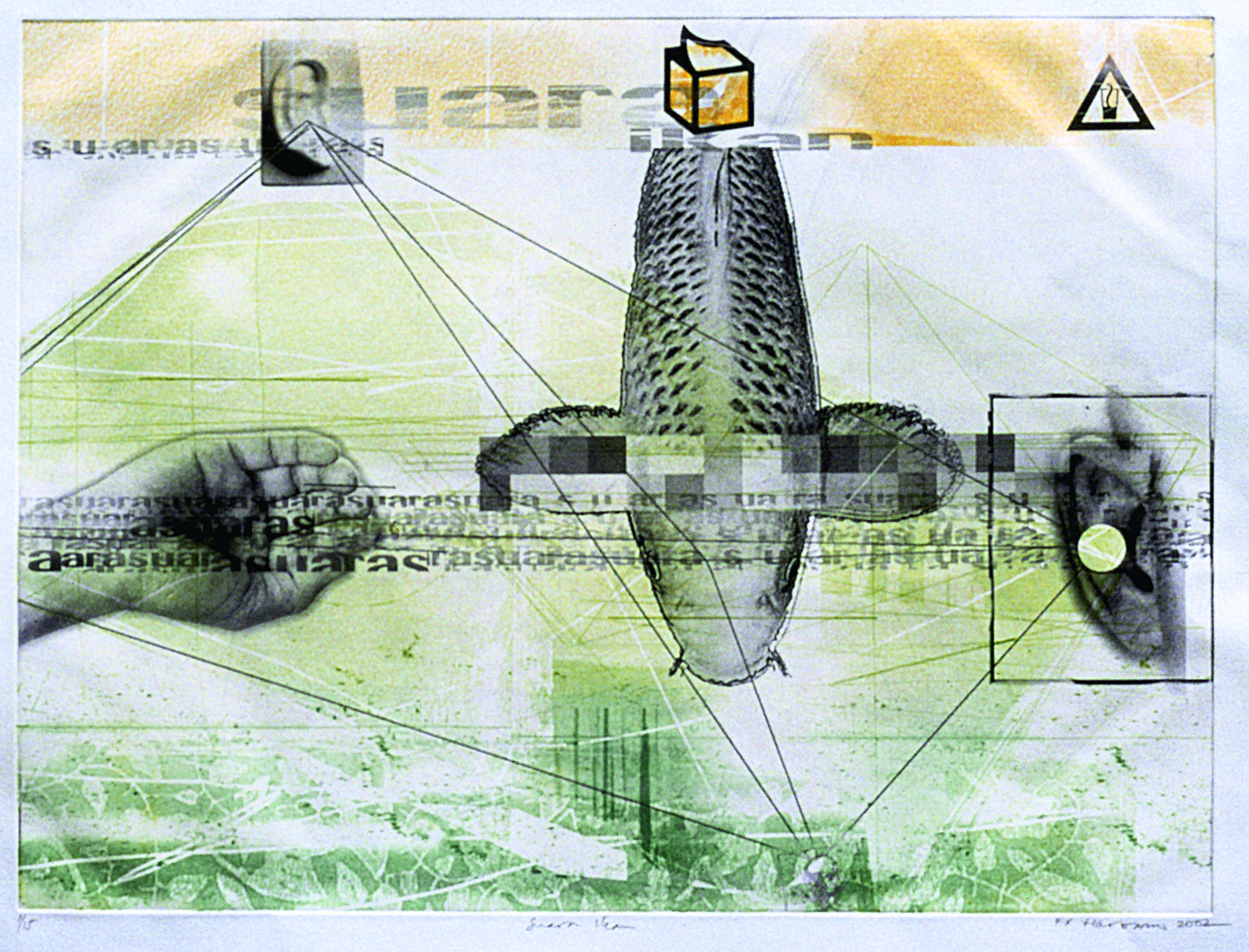

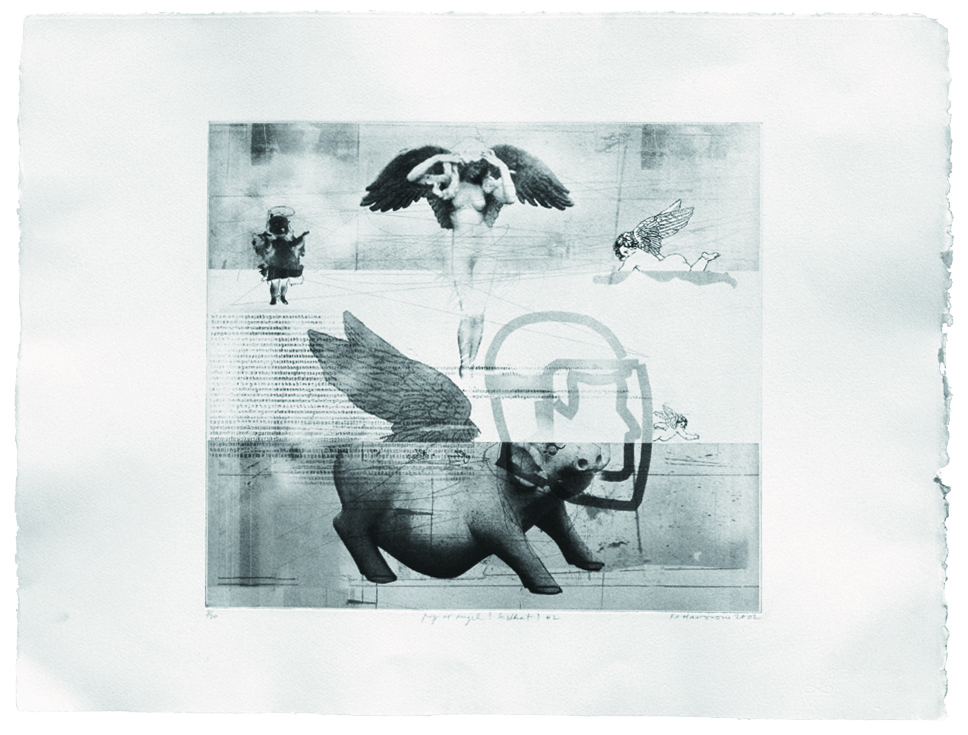

Toy pistols in the hands of female robots and aimed at a village woman walking confidently with dark and covered face in the work “Super Women” (2001). These figure walk pass two female robots tailing her in their tough virtual image in the left and right. A playful situation emerges from this work. Which one is the super girl in this picture? Which one do we consider as real? By manipulating photo with computer Harsono can soften or otherwise sharpen the picture as well as playing with many visual effects. But abstract effects looks very constrained in his works, so that the intended signs always look obvious, as in “Pig or Angel? So What?” (2002).

The image of Balinese pig sculpture with wings and transparent helm, the mouth blasting out from it. Icons of angels lining neatly blowing their trumpets towards the pig’s ears. The clearer the identity of the “pig warrior” looks in its strange world, the clearer is the paradox for us as the audience. This work is according to Harsono triggered by the question on what is good and what is bad that is becoming, either for the society or by the leaders, harder to determine.

In “Harga diri”/Pride (2002), FX Harsono present several self prtraits hiding half of his face while sticking out his tongue. He places in front of his skinny figure, several jumping icons: fish, barcode, a ball made of complicated thread, figure of a victim and sandal.

If we can recall his line of thoughts on self identity that does not root in one “original” culture, Harsono’s criticism can be narrowly interpreted as: is the judgement towards minority groups can be easy everywhere? Yet Harsono’s self portrait may not be intended as Harsono.

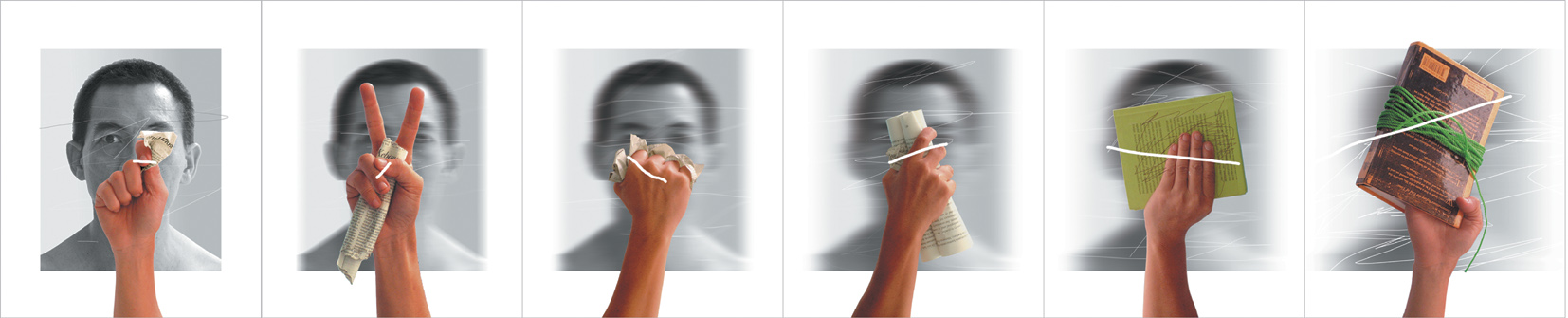

In “Cogito ergo sum” (2002-2003) consisting of 6 pictures, he again present his self portrait in a monotony of color focused on the face. The faces are covered by an order of fingers that compose an unreadable configuration. By using a soft blur technique, his face slowly expand, flat and turns into shadow. The hands are decorated with cuts from newspapers or books that stimulate us to investigate or think: But why does this cogito subject, that so far thinks very hard ceases to exist, and even dissolves?

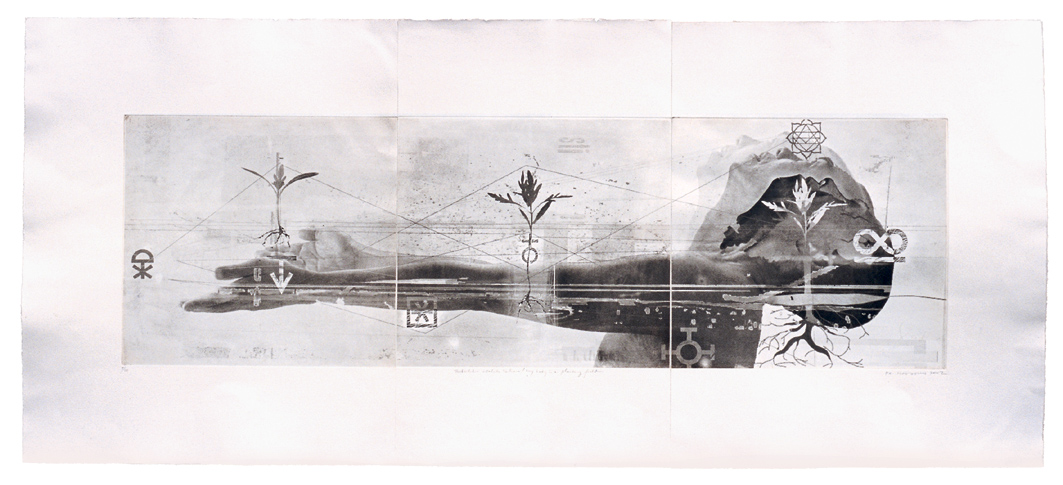

“Tubuhku Adalah Lahan”/My Body is a Field (2002), is his other photo etching work. The artist is shown as lifting his head as strong as possible and stretching his arms forward as straight as possible as a gesture of total surrender. Plants can still live along his arms and on his head with their root, growing but ripped up at the same time. But that is also how his head is supported or leaned, floating a twist of symbol of limitlessness.

In “Blankspot on My TV” (2002-2003), Harsono immortalized several celebrity talking in various TV programs he watches at home. He placed their photos to his works that looks like a television. But he gives white dots – like a hole or floating ball – in the mouth of every speaker so that there will be disconnected lines. For several years since his early years as an artist, Harsono sceptically decided to quit reading any media. He now makes 20 enthusiastic series of work about the role of television and intends to “stop” the opinion emerging from there. He seems like somebody still enjoying television – often considered as the core of postmodern culture – but what he enjoys more is swimming in the space of TV simulation. How the audience places themselves in front of TV screen: whether the presence of this medium has enriched or emptied and made a hole in our imagination?

Vito Acconci, a video artist once wrote about television audience that acts as if “owning a television within themselves, like cancer. (…) Television audience has also been replaced and displaced… With television people are finally able to become a “model figure”, but the person is a model, a nonself. People functions as “screen”, a simulation of self… Television strengthens the diagnosis that the border between the inside and the outside is blur: the diagnosis of “self” as concept is old fashioned…11

The works “Displaced #1,# 2 and #3 (2003) also provokes us about “self. Harsono present his self portrait wearing black plastic bag. His naked body is pictured sitting down quietly holding plastic flowers. At first in “Displaced #1” the figure is presented as mere outline, together with Chinese characters, so weighed with stigma, that mean “double happines” as the background colliding with the body. Two other series (#2 and #3) is moving towards more realistic image to emphasize the real paradox: a desaparecidos (victim of forced disapearance) and a bride in waiting. Rather than experiencing double happiness as the Chinese bride expected, “double happiness” is a double discourse about body being celebrated and body being condescended.

Harsono has created a “little monument” as a memorial of the downfall of a leader after having been in power for 32 years, that “honorably” created enormous reservation within his self, both as a citizen and an artist. The work is a serial stamp parody entitled “Republik Indochaos” (1998), an unofficial stamp without the publication of its first day cover. Republic is res-extensa, public spaces where the supposedly-solid, existing identity of the cogito is once and for all mortgaged. But the space is now inside a chaos everywhere, and the cogito who thinks dissolved… No more authority of the single guarantor of identity or body. An artist who is aware of these shifts will be challenged by the heat of questions slowly begin to burn places where one places one’s bum.

Hendro Wiyanto

- Quoted from Renato Poggioli, “The Concept of a Movement”, The Theory of The Avant Garde, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1968[↩]

- See Ignas Kleden, “Membangun Tradisi Tanpa Sikap Tradisional”, dalam “Sikap Ilmiah dan Kritik Kebudayaan”, LP3ES, 2nd Edition, 1988.[↩]

- FX Harsono, “Dua Pola Pikiran dalam Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru”, Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru Indonesia, editor Jim Supangkat, 1979).[↩]

- FX Harsono, “Upaya Mandiri Seni Rupa Pembaruan”, Kompas, 25 October 1992[↩]

- Moelyono, “Upaya Hidup Seni Rupa Pembaruan”, Kompas, 11 October 1992[↩]

- See Harsono, Gendut Riyanto dan Winardi, “Seni Rupa kembali ke Masyarakat”, discussion paper, 5 July 1985[↩]

- FX Harsono, “Mengapa Seni Rupa”, in “Suara’, Pameran Seni Rupa Kontemporer FX Harsono,Gedung Pameran Seni Rupa Depdikbud, Jakarta 23-29 July 1994 (catalog)[↩]

- Quoted from Jean-Fracois Lyotard, “The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge”, in Lawrence E.Cahoone, From Modernisme to Postmodernism: An Anthology (Blackwell Publishers Inc., 1996).[↩]

- Tim Gabungan Pencari Fakta (TGPF)/Joint Team of Investigation noted 1200 victims were scorched, 8500 buildings and vehicles burnt, more than 90 Chinese women raped and harrassed during 13, 14, 15 May 1998 riot in Jakarta. After 5 years the case has not yet been associated with any suspects. (See: TEMPO, Five Year of Reformasi, 25 May 2003).[↩]

- See: Joseph E. McHugh, “Connecting the Dots: Sigmar Polke’s Rasterbilder in their Sociopolitical Context”, in Sigmar Polke, Back to Postmodernity, Liverpool University Press, 1996.[↩]

- Vito Acconci, “Television, Furniture,and Sculpture: The Room with the American View , in Illuminating Video, Aperture/BAVC, 1990.[↩]