Writing in The Rain

Washed-Away Memories

A name is a very personal form of identity. Personal means individual and private. However personal identity becomes a collective problem when it is no longer felt only by individuals but is also shared by them as a group. The problem of personal identity becomes the identity problem of an ethnic group, and is very likely a global phenomenon.

A name points to a person’s identity and is personal by its nature. Linguistically, the way a name is given, the grouping of names, all point to the identity of specific ethnic groups. Chinese names are different to Javanese and Dutch names. There are some who argue that naming is merely making a mark or sign. But there are also those who perceive a name as giving meaning to his life.

Every newborn receives a name from their parents. So is the case with myself. I received a name according to the culture and lineage of my parents as Tionghoa or ‘Chinese Indonesians’. I was named Oh Hong Bun. This was a name that was stuck to me until I was 18 years old.

‘Oh Hong Bun’, in the Hokian dialect, is also ‘Hu Feng Wen’ in Mandarin. ‘Oh’ or ‘Hu’ is the family name, which has the connotation of a good luck charm believed to bring fortune to its bearer. Hong is harvest and Bun is literature or the arts. We may translate the name as someone who is prosperous artistically, abundant with beauty, or someone who harvests words and literature.

Since 1967, based on the “Presidental Cabinet Decision No 127/U/Kep/12/1966” I was made to give a testimony of my own will towards changing my Tionghoa name to an Indonesian one. According to this letter of mandate, every Indonesian citizen of Tionghoa descent is ‘advised’ (read: forced) to change their original names to the names that an ‘authentic’ Indonesian person should have.

My 18 year old self was subject to this new regulation. I was then named Franciscus Harsono. Franciscus was my baptized Catholic name, which was given by my mother. Harsono was a name that I found for myself.

Tionghoa names indicate that a group of people who are not ‘real’ Indonesians, as foreigners, bad, unnationalistic. To ‘appear authentic’ these names must then be changed to Indonesian names. The term ‘authentic’ was constructed as good, original, nationalistic and part of the majority.

***

Based on historical finds, it is presumed that the Chinese arrived in Indonesia since 1 – 6BC. The arrival of the Chinese was initiated by seatrade. It wasn’t until the Airlangga empire in Tuba, Gresik, Jepara, Lasem and Banten that there are proofs of the existence of Chinese colonies there.1

From these historical evidence, it is apparent that the Chinese have been in Indonesia for a long period of time. However the lenghty relation does not necessarily imply that the relation between the Chinese and the Indonesians were a harmonious one. Political problems from the Dutch era also influenced the powerful discordances that permeate this relation.

I don’t know exactly when my ancestors first set foot in Java. However, I can gauge that I may be a fourth or fifth generation. Even my grandmother from my father’s side and great grandmother from my grandfather’s side are Javanese. Yet this does not affect my position as an Indonesian who’s still considered as ‘inauthentic’, for bearing a Chinese name.

Indonesia is made up many different national tribes. However, in the case of the Chinese, there is an affinitity of the idea of an ‘ethnonation’ to the concept of nationahood, pivoting on the notion of the indigeneous. ‘Ethnonation’ refers to the concept of being an Indonesian based on ‘race’ or ‘ethnicity’. Even though the Tionghoa have become Indonesian citizens, they still stand aside from the indigeneous, considered a stranger, even though elements of ‘the stranger’ are only very faint in him. Citizenship is considered differently to nationhood, to include civil rights. The slogan Bhinneka Tungga Ika only applies to indigeneous Indonesia people, and not for the Tionghoa.2

***

During the Soeharto era, my artworks were orientated towards social and political problems. I was also an active participant in an NGO that worked to defend the rights of people who were repressed by the Soeharto regime. However, when the era collapsed, I began to question my own identity as a Tionghoa person who continued to be discriminated by the Soeharto government.

Since the fall of that government, reformations occurred in all aspects of life, especially in politics. In 2002, the then president Abdulrahman Wahid oversaw significant changes, not to mention the abolishment of the previously mentioned law, and the implementation of the Presidential Decision Memo Number 6 Year 2000. With this new regulation, Imlek-Capgome was allowed to be celebrated openly, without the interference from the arms of the law.

Ever since then I continued to look back at my own history, my family’s history and the history of the Tionghoa from my birth town, Blitar. The memory of my own Chinese name that hasn’t been used since 1967 returned. I tried to remember and to scroll this name down. Remembering my ancestral history, remembering my own name was an effort to grapple with identity and to dig deep for cultural roots that have been yanked out for 35 years. This effort was the source of my inspiration in creating my work.

Although political changes for the better have occurred and there is now a greater sense of freedom than before, the attempt to search for identity and cultural roots remain a difficult task to do. Challenges and suspicions continue to be felt, from the indigenous Indonesian as well as the Tionghoa themselves. They doubt my nationalism by questioning my identity. Yet I continue to work and research into my own as well as my familial history and the Chinese Indonesians in the process of creating an Indonesian nationality. To acknowledge history does not imply defeat. Acknowledging and remembering do not imply that one has betrayed a sense of nationalism. Remembering puts identity as a link that connects past socio-cultural norms in supporting the future, for someone who accepts plurality as part of national wealth.

Text in the arto works.

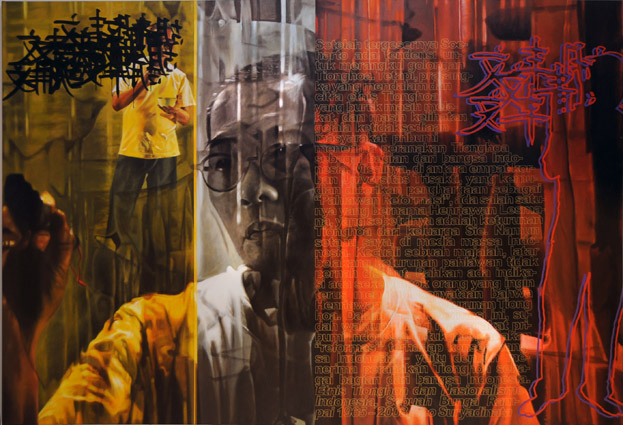

Text in : Screen Shot From Writing In The Rain # 1

…the need for standardisation and control in regulating the change and addition of surnames, as a step to homogenise Indonesian citizens about the change and Addition of Surnames (emphasis added). The regulation reflects pressure, under both Soeharto and Soekarno, for ethnic Chinese who are citizens to adopt pribumi-sounding “indigenous Indonesia names… names in conformity with those customarily used in the Indonesian community”, as a token of “the process of assimilation”. “Alien” Chinese are thus not allowed to change their names. This, of course, makes them more easily identifiable, although some ethnic Chinese citizens have resisted the pressure. “Reconstituting the Ethnic Chinese in Post-Soeharto Indonesia, Law, Racial Discrimination, and Reform”, by Tim Lindsey, at the book of “Chinese Indonesians, Remembering, Distorting, Forgetting”.

Text in : Screen Shot From Writing In The Rain # 2

Since the shift from the Soeharto regime there is a growing tendency to embrace the Tionghoa ethnic group . However, deep-rooted suspicions and the negative connotations attached to this particular group remain, and make themselves apparent in the various forms of resistance that continue to exist from the indigenous people in accepting the Tionghoa hybrid as part of the nation. For instance, one in the four victims of the Trisakti Tragedy, now referred to as Reformation Heroes, is a man named Henriawan Lesmana, from the Tionghoa lineage of the Sie family. Yet to my knowledge, in Indonesian mass media, apart from one magazine, there is no mention of the hero’s ethnic background. There even appears to be an indication of attempts to cover up the fact that Henriawan was a Chinese Indonesian. In this Reform Order, it is timely that the indigenous people of Indonesia ‘reform’ their sense of nationhood, by accepting the Tionghoa as part of the nation.

Tionghoa Ethnicity and Indonesian Nationalism, An Anthology 1965 – 2008, Leo Suryadinata.

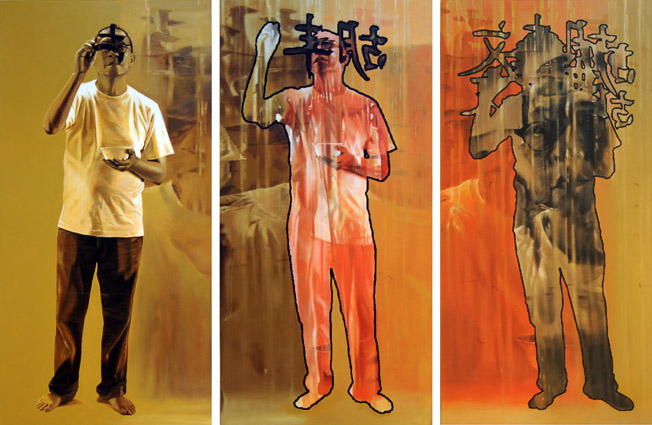

Text in : Screen Shot From Writing In The Rain # 4

Indigenous in Indonesian name is the names inconformity with those customarily use in the Indonesian community

Text in : Screen Shot From Writing In The Rain # 5

I am a mark from the divine

I am the past and the future

I am a mark thus I exist

I exist from a wound, joy and victory

I appear through dark and light

Mitha Budhyarto – Translation