The Erased Time

Erased Time, Disappearing Traces

An old photo album in the family room

One day in the mid-seventies, when Harsono was still an art student in Yogyakarta, he came home to visit his father. The old man had just been freed after having been incarcerated for a year. The reason? Due to a series of events that were rather coincidental in nature, the father was seen as linked with a “dangerous” psychic in the small town of Ponorogo (East Java). A lot of the “new” nationalists that the authority deemed as leftist (and therefore culpable) happened to be the clients of this charismatic clairvoyant. Apparently, in all levels of the Indonesian society, the link between politics and paranormal practices is likely. At least that is what we often hear of in Indonesia.

What was the father’s “wrongdoing”?Well, Harsono’s father made iron-clad wooden sticks that could be considered as amulets after Mbah Suro, the psychic, “filled it with supernatural forces”. The charismatic figure—whom many thought as able to distribute well-being, wealth, and power—was apprehended, along with all the people around him. Naturally, Harsono’s father was arrested as well. That, you know, was the time when the New Order regime was in its adolescent stage, after having successfully toppled the Old Order.

It was when Harsono came home to Blitar that he rediscovered the old photo albums in their living room. All members of the family—including Harsono—had often flicked through those albums, and perhaps even memorize the pictures inside out. Still, no one had ever questioned a series of peculiar photographs there.

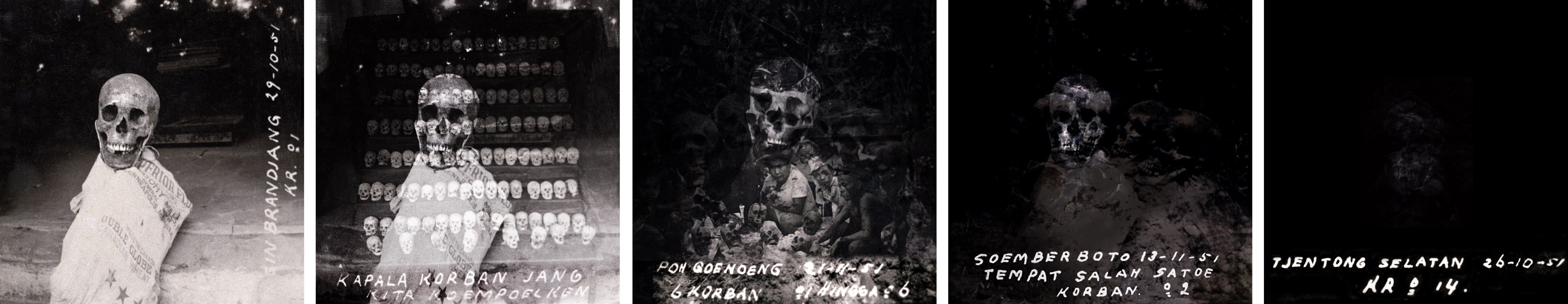

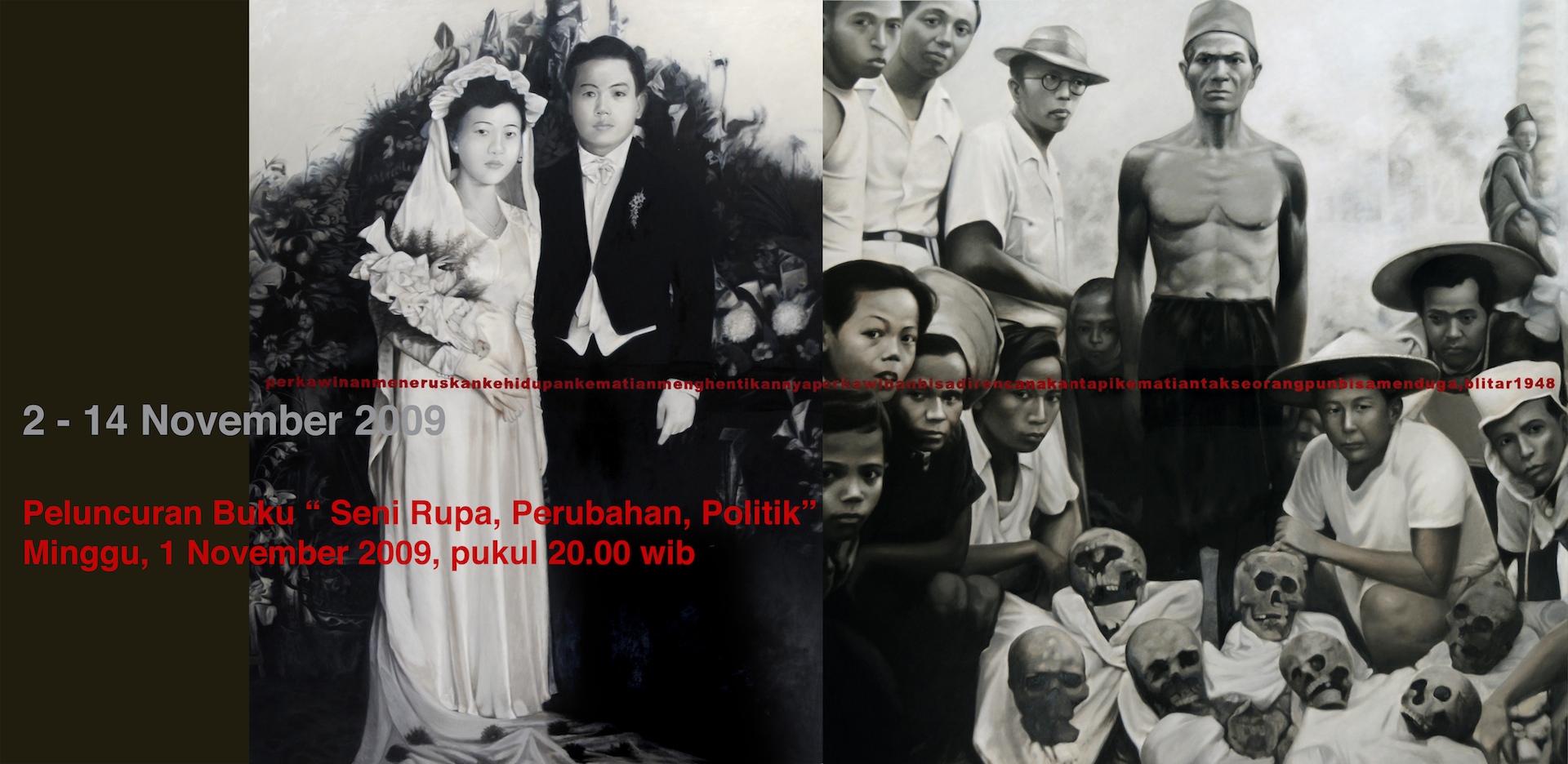

Amongst the family pictures, Harsono found intriguing photographs—around eighty pieces of them. The black-and-white pictures depicted the efforts of a group of people to exhume long-buried bodies of the Chinese people that had been the victims of the mass killings in 1946 – 1948. Those were the historical pictures taken by Harsono’s father.

Harsono’s father, Oh Hok Tjoe—who subsequently changed his name to Hendro Subagio—was a photographer in Blitar. In the early fifties to the mid-sixties, he owned the “Atom” photo studio, the most popular photo studio in town at the time. Everybody who wished to look cool—the general families or those who were members of the traditional wayangtroupe—would come there to have their pictures taken.

The pictures were apparently related to the Chung Hua Tsung Hui organization (the CHTH) in Indonesia. It was an umbrella organization that housed the different associations of the Chinese community in Indonesia, be it those whose members had already affirmed their nationalities as Indonesians, or those whose members were yet to become Indonesian nationals (i.e. they were still known as “foreign Chinese”). The CHTH was established to serve as the counterpoint of the representatives of Chinese-descendants in the various conferences initiated by the Dutch during the post-independence “political actions” in 1947 – 1949. The establishment of the CHTH had been initiated by the government of the newly independent Republic of Indonesia. The organization’s specific task was to serve as a consultant to the government in dealing with matters related to the Chinese community in Indonesia.

In 1951, the organization began the effort to exhume and record the victims of mass killings against the Chinese communities in several towns on Java. The CHTH—through its branches in many Indonesian towns—tried to track down the identities of the victims that had been murdered during the chaotic years. They made records of the number of the victims, contacted family members who were still searching and trying to remember, and then buried the victims again in appropriate manners. Harsono’s father was involved in this group’s acts of benevolence.

Some of the photographs were dated October – December 1951, pointing at the time of the exhumation, or what the locals called “ndudah”. Through the pictures, parts of the dark history that were almost laid to rest, were beginning to be disclosed.1)

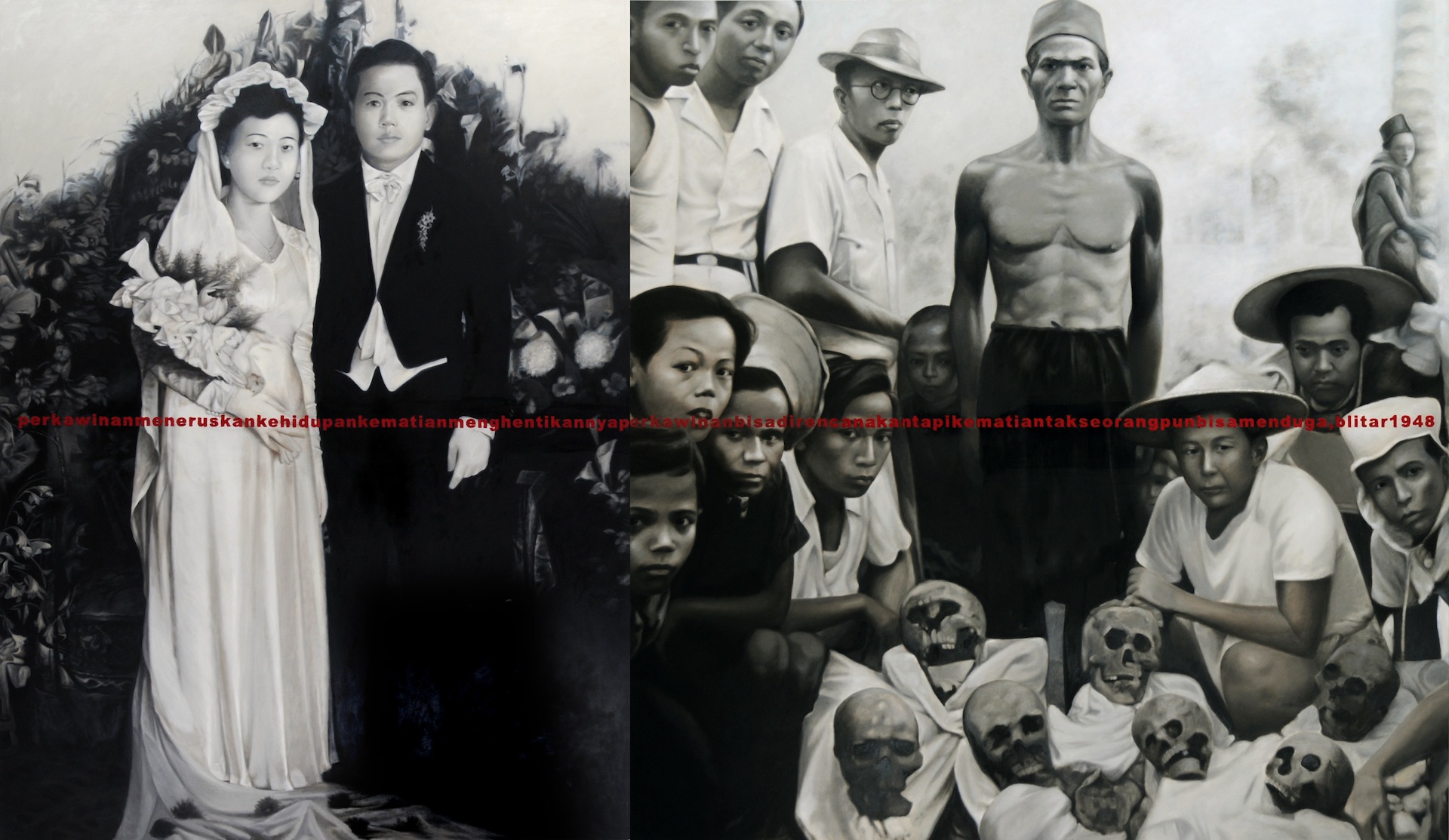

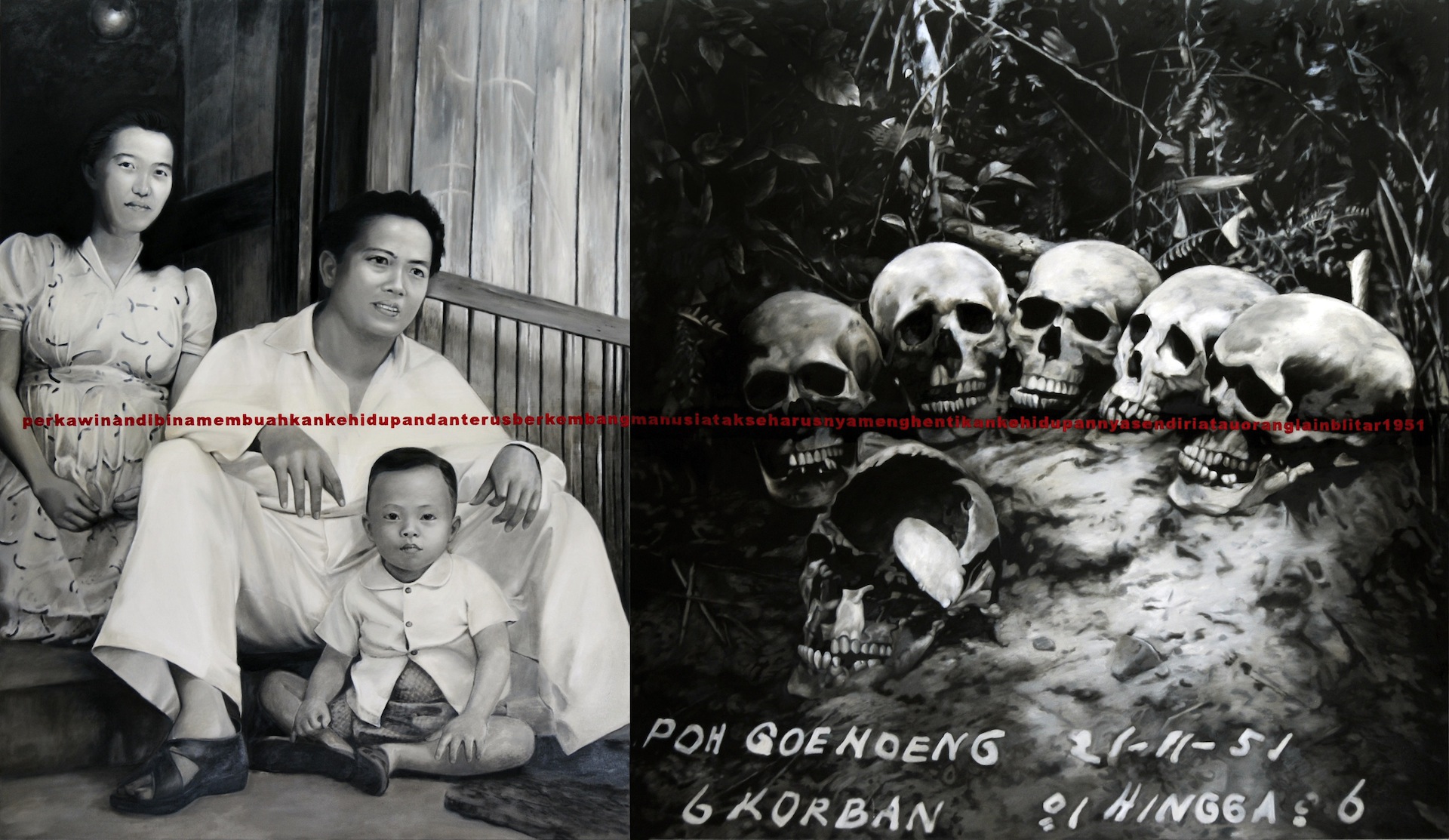

Harsono’s encounter with those photographs took place scores of years ago. One day, he became aware that the pictures were invaluable historical records, too precious to be forgotten. He kept the albums well; it was as if those pictures were even more valuable than the photographs of his own family. Later on, in one of his works, he would unexpectedly put the two different kinds of pictures side by side: the photographs of the exhumation seemed to give a new identity to the pictures of his family members, who had survived the chaotic period. Harsono himself was still in his mother’s womb when the killing fields still consumed the victims’ blood. Life has its way to survive. Unfortunately, his father never talked a lot about the pictures. A friend of Harsono’s, a journalist, once attempted to interview him to no avail.2)

The authoritarian regime that had put Harsono’s father behind bars was toppled in 1998. The father died not long after, in 1999, carrying with him the stories behind the unearthing of the victims’ bodies. What happened with the victims before they were murdered? Where did those murders take place? Who were murdered, actually, and how?

In the tumultuous years after the New Order regime collapsed, a series of questions, which had seemingly been mere personal matters, started to surface and bother Harsono. He was haunted by the old pictures that his father had taken. He maintained that this had nothing to do with any feeling of bitterness that he might have toward the regime that had incarcerated his father.

The photo albums that had for so long been left in his old house at the Tjoe Tin Alley, Blitar, seemed to have given him a new assignment.

What is your name?

What did they call you at home?

Ong.

What was the full name?

Oh Hong Boen. I don’t know how they got to call me “Ong”.

Did you know what your name meant?

Nope. Later they would tell me, though. “Hong” means affluent, rich… “Boen” means literary, art.

Who gave you that name?

I don’t know. Today, the only Chinese words I know are those in my Chinese name. I can only write my name.

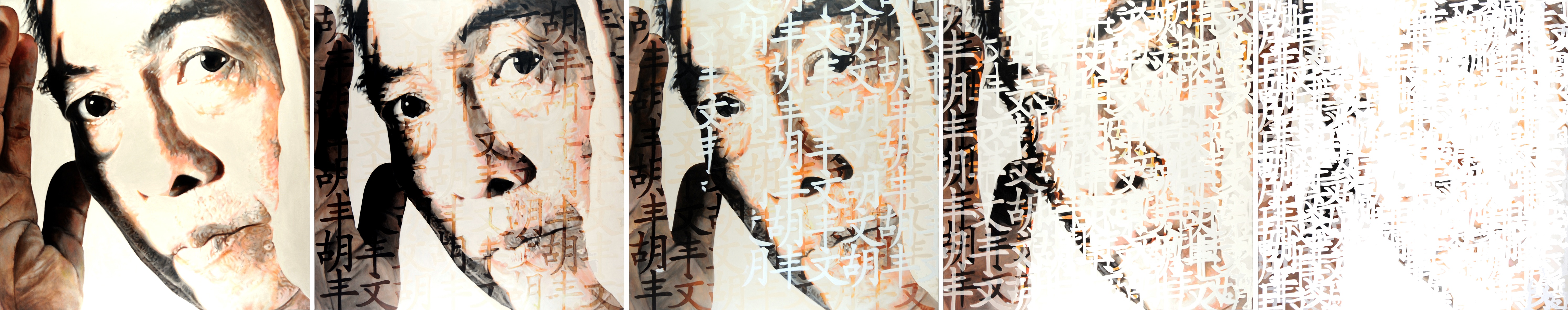

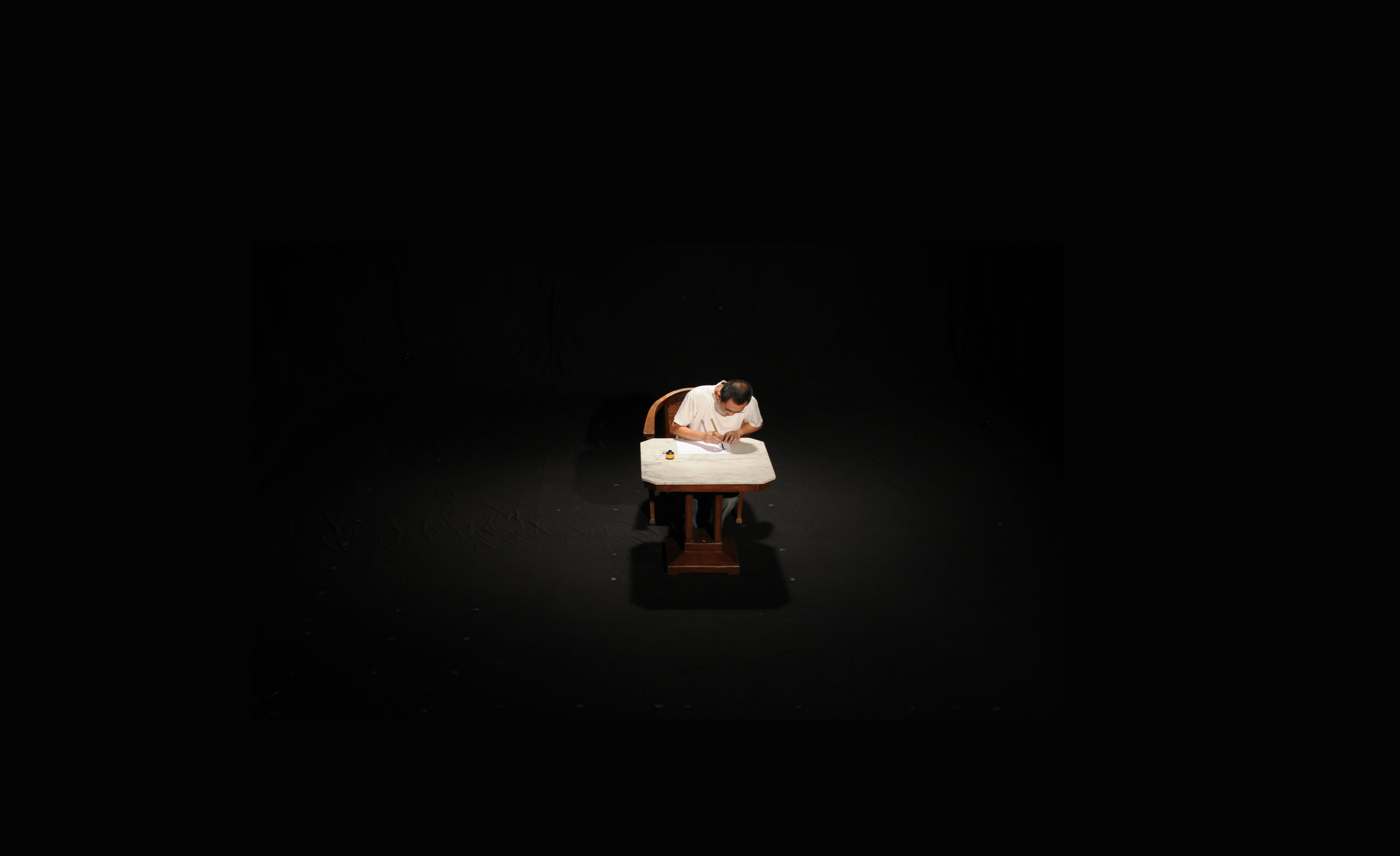

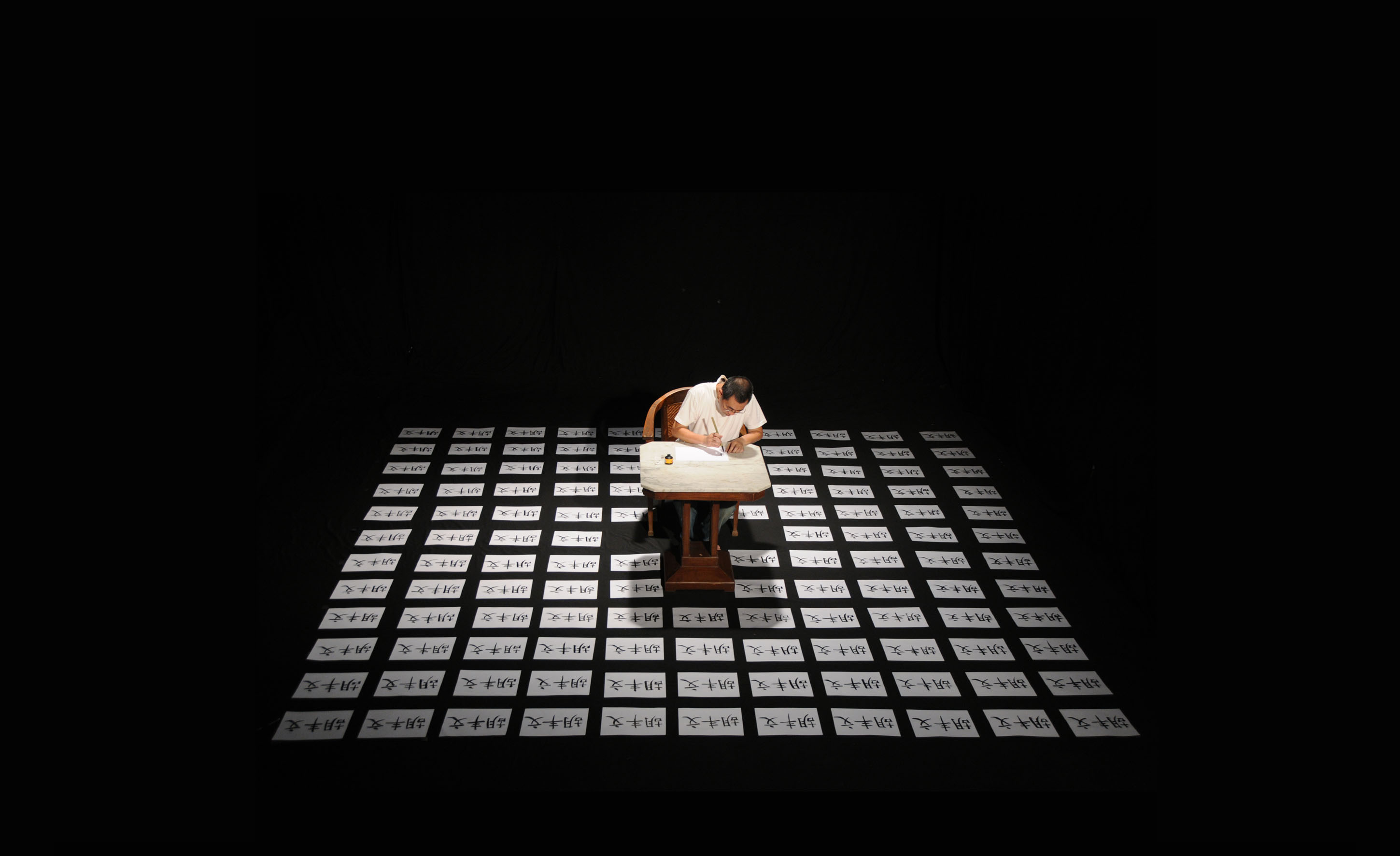

He then tried to re-write his name. Again and again. He went on, seemingly unstoppable. He tried to recall how to write the characters that today felt so alien to him. The characters that he, scores of years ago, had learnt about and mastered. The shapes and sounds of these characters are rather different from the three syllables in his name in Latin alphabets, but the meaning remains the same.

That was his own name, given to him once, a long time ago. The name was there to show who he was. One day, however, the name was like a trace that must be erased and even forgotten. Now he wants to rediscover it, recapture the time, had it all been possible.

It has been so long—very long, indeed—since he heard his old name was uttered, by himself or by someone else. He no longer goes by that name. He does not know where that sound has gone—the sound of his name. He does not know where those characters have gone. He can only remember them vaguely. He does not know what his name today means.

Words disappear, but the text remains.

He thus tries to write them again.

Home? Home, where?

“As soon as dusk came, there would be so many kids from another village, which was rather far from ours. They went to the mosque through my village. If we still hung around, they would call us names. They would say, ‘Chinese, Chinese… go back home!’ Sometimes they would throw pebbles at us, so much so that we always felt we had to be home by six in the evening…”3)

Harsono’s efforts to revisit his past, his family, and reconsider the influence of his education, language, and environment during his childhood constituted his desire to understand or become aware of the problems of his identity.

Where should one begin to dissect the issue of one’s identity? Is identity a given, something that is assigned to us since we are still in our mothers’ wombs? Is it a kind of a “religion of seed” that is related to the belief about the superiority of a certain race? Or is it about a never-ending search from the day we were born to the day we die? Is identity a cultural problem, or is it political? What kind of identity politics that keeps on generating violence and causing death?

For Harsono, identity is an issue because he has not been able to affirm it; he could only accept what others had assigned to him. Being born from Chinese parents had not been an option, and was apparently not necessarily a good fortune. There was the chaos generated by the Government Regulation No. 10/1959 that obliged all Chinese retailers to close their businesses in the remote Indonesian regions. The chaos almost forced Harsono’s parents to return “home” to China. But what did it mean for Harsono, and for his family, to “go home”, yesterday and today?

“My father was getting ready to go home. As for myself, I couldn’t get it. Home? What did he mean, home? I didn’t even understand any Chinese words. Still, my father was getting ready. He bought warm clothes, asked the tailor to make winter clothing… We were going home, but we didn’t know where home was…” Harsono reminisces.

To be a Chinese—or a member of any other ethnic group—apparently means to be ready to experience a kind of “accidental racism”, which could mean being jeered at, hated, or honored. This is all because people think that they belong to certain races, and even believe that there is such a thing as the essence of a race.

“Ethnicity never flows in our blood. It is not inherited from parents to children. Objectively, naturally, or biologically speaking, there is no such thing as ‘a Chinese.’ Or ‘an indigenous’ for that matter. What indeed exists is a person that has been ‘made Chinese’ through social processes… Women were raped in May 1998 not because they were Chinese; rather, they became Chinese because they had been raped.”5)

Harsono had even been scared before; he feared that he might not become a part of “Indonesia.” If he is not a part of Indonesia, where does he belong to? Where exactly is Indonesia within him, and where does he stand in Indonesia? He must deny something within him to become “Indonesia.” But he does not know for sure what it is that he must deny. By denying it, however, he inflicts a wound in the deepest part of him. It seems that it is only through that, through fear and the ‘politics of denial’, that the way is formed to pursue his identity.

In one of his works, exhibited in 2003, Harsono began to present his family pictures—the pictures of his parents’ wedding, to be exact. He also presented pictures of himself. “I” or “myself” was the realm of contention between denial and acknowledgement, and it has become even more important to him after 1998.

He knew that something was missing in the “I” or “myself.” He then started to become curious about what one calls as ‘hybrid.’ A long time ago, his grandmother used to hang pictures of Soekarno, the communist leader DN Aidit, and Jesus on the cross in the bedroom. She went to church on Sundays, and practiced Islamic mysticism on Fridays.

There were schools practicing the Dutch lifestyle, attended by Chinese children. There were Dutch table manners, practiced by Indonesians with Chinese looks. His mother was a Catholic Chinese who went to the Holland Chinese School. Harsono himself used to go to a Chinese school and had a Chinese name until he reached the fourth year in the elementary school, and then he moved to a Catholic school where he had an Indonesian name and had the identity of a Catholic boy. Everything is mixed up. There is not one single structure that makes people trust a monolithic identity. A monolithic identity is a weapon to kill the others, the ones that are not like us.

Names and stories

Sixty years have passed since his late father, along with the Chung Hua Tsung Hui organization, exhumed the bodies and buried those scattered bones again.

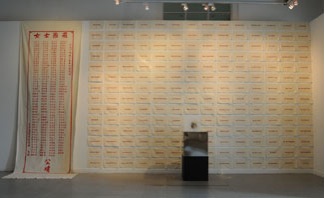

Now, older than his father had been at the time, Harsono returns to the place where the victims were properly buried. The graves had names, in keeping with the original names of the victims. The victims’ family members can visit them again. Their names and their stories live in memories. They are no longer anonymous victims, but rather victims with names. There are 191 names in total.

People can become victims because of their names.

The names of the victims are written on the graves. The characters remain alien and meaningless to Harsono. Violence, murder, and torture, however, always have names for him. Harsono, the baby in his mother’s womb, had survived the killing field, and now cannot immediately believe the claim that grand narratives are done for, meaningless, limp.

He meets the locals who now bravely show him where the killing fields had been. They know that people had been massacred, somewhere, sometime ago. One day, another group also tries to exhume the bodies. They recount the stories with the help of the surviving memories—what else if not to narrate stories, for the time past, for the almost disappearing traces of events?

I find a quote from Bateson, I don’t know from where: “What is important in a story, what is true in it, is not the plot, the things, or the people in a story, but the relationships between them.”

Hendro Wiyanto

Exhibition curator

Notes:

- Harsono had learnt about the killings from a book by Benny G. Setiono, Tionghoa dalam Pusaran Politik: Mengungkap Fakta Sejarah Tersembunyi Orang Tionghoa di Indonesia (The Chinese in the Political Vortex: Disclosing the Hidden Facts of History about the Chinese in Indonesia), Transmedia: Jakarta, 2008. Benny Setiono considers the event as “an overkill of the independence revolution in 1946 – 1948.”

Benny writes: “Arson, looting, rapes, and murders took place incessantly in many places on Java and Sumatra until the end of 1949. Shocking events took place in East Java, especially after the inmates at the Kalisosok prison in Surabaya were released, fully armed and recruited as soldiers of fortune. They were allowed to do anything to help assist free the towns, in support of the scorched earth policy taken by the Republic of Indonesia. Several regions where the Chinese people became the main victims of looting and murders were Kertosono, Nganjuk, Caruban, Madiun, Blitar, Tulungagung, Kediri, Wlingi, and Malang.”

(See Benny G. Setiono, Tionghoa dalam Pusaran Politik: Mengungkap Fakta Sejarah Tersembunyi Orang Tionghoa di Indonesia [The Chinese in the Political Vortex: Disclosing the Hidden Facts of History about the Chinese in Indonesia], Transmedia: Jakarta, 2008, especially Chapter 31, pp. 583 – 619)

The book also published some photographs taken by Harsono’s father about the exhumation; i.e. on page 626 – 628.

- This journalist friend of Harsono’s was Stanley Adi Prasetyo, who also opened Harsono’s exhibition at the National Gallery of Indonesia.

- Interview with FX Harsono, May 19, 2009

- The belief that the Chinese seed or “tsing”, no matter through which womb, will invariably give rise to a Chinese person. Pramoedya Ananta Toer has written about this in his well-known book, Hoakiau di Indonesia (Garba Budaya: Jakarta, 1998, p.222)

- Ariel Heryanto, “Rasisme Tak Sengaja” (Accidental Racism), Kompas daily, February 6, 2004.

- I will always remember my late mother, who, every time she went to some new place, would say, “It’s safe here” if she saw another Chinese there. Did she feel safe because she saw a fellow Chinese? Was the fact that there was (still) a Chinese living in that place a mark of well-being, as a Chinese person survived and seemed welcome there? Or were those words a mask for her sense of insecurity due to her undeniably Chinese identity?